The concept of a biennale has long been associated with physical spaces—pavilions, galleries, and cities teeming with visitors. Yet, the emergence of the Metaverse Biennale challenges this very notion, proposing a radical reimagining of what it means to curate and experience art in a fully virtual environment. This experiment in digital curation is not merely a replication of the physical art world but a bold exploration of the unique possibilities offered by immersive technologies. Artists, curators, and audiences are navigating uncharted territory, where the rules of engagement are rewritten, and the boundaries of creativity are stretched beyond conventional limits.

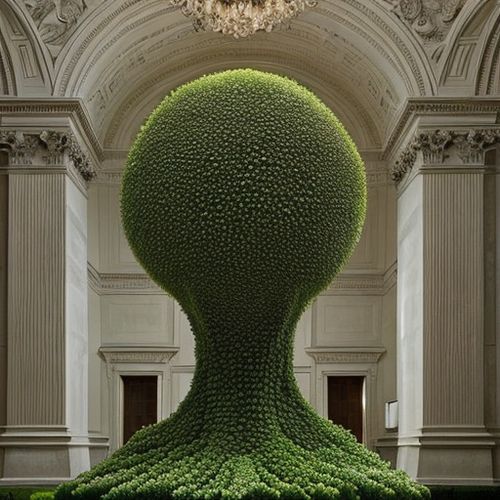

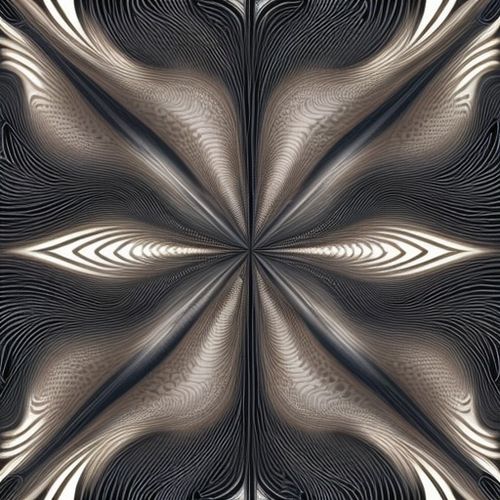

At the heart of the Metaverse Biennale lies the question of how art can transcend the limitations of physicality. In a virtual space, artworks are no longer confined by gravity, material costs, or geographic barriers. Sculptures can float in mid-air, paintings can shift forms dynamically, and installations can respond to the presence of visitors in real time. This liberation from physical constraints opens up a playground for innovation, where the only limit is the imagination of the creators. The biennale becomes less about the objects themselves and more about the experiences they generate—a shift that redefines the role of both artist and viewer.

One of the most compelling aspects of this virtual experiment is the democratization of access. Traditional biennales often require travel, visas, and financial resources that exclude large segments of the global population. The Metaverse Biennale, by contrast, is accessible to anyone with an internet connection and a compatible device. This inclusivity extends not only to audiences but also to artists who might otherwise lack the means to participate in prestigious international exhibitions. Suddenly, a creator from a remote village can showcase their work alongside established names, and a student in Buenos Aires can critique a digital installation crafted by a collective in Tokyo. The playing field is leveled in ways previously unimaginable.

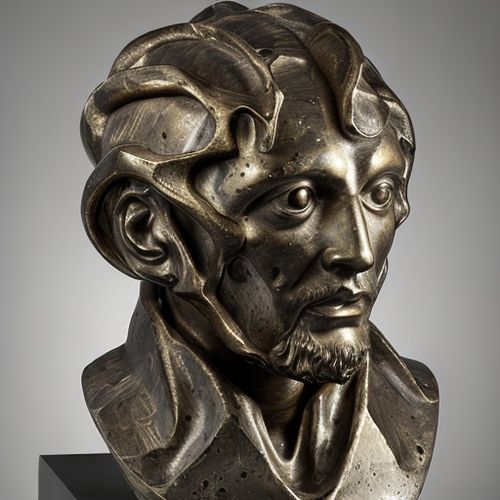

Yet, the virtual nature of the event also raises pressing questions about authenticity and aura. Walter Benjamin’s famous essay on the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction takes on new relevance here. Can a digital artwork possess the same aura as a physical one? Does the absence of a tangible object diminish the emotional impact of the piece? Curators of the Metaverse Biennale grapple with these questions, experimenting with ways to create a sense of presence and uniqueness in a space where everything can, theoretically, be copied and shared infinitely. Some turn to blockchain technology to mint limited editions of digital works, while others focus on crafting one-of-a-kind interactive experiences that cannot be replicated.

The collaborative potential of the metaverse further distinguishes this biennale from its physical counterparts. In a traditional exhibition, artworks are static, and interactions between visitors are often limited to hushed conversations or curated talks. In the Metaverse Biennale, participants can co-create, modify, or even remix the artworks on display. A visitor might add a layer of sound to a visual piece, or a group might collectively alter the parameters of an algorithmic sculpture. This blurring of the lines between creator and audience challenges hierarchical notions of authorship and invites a more fluid, participatory mode of engagement. The exhibition becomes a living, evolving entity rather than a fixed collection of objects.

Technical challenges, however, loom large. The infrastructure required to support a seamless virtual biennale is immense—high-speed internet, powerful servers, and sophisticated software platforms must all work in harmony. Latency issues can disrupt immersive experiences, and not all participants have access to cutting-edge VR equipment. Curators must strike a delicate balance between pushing technological boundaries and ensuring accessibility. Some opt for browser-based platforms that require minimal hardware, while others create high-fidelity environments designed for those with advanced setups. The tension between innovation and inclusivity remains an ongoing negotiation.

Critics of the Metaverse Biennale argue that the very absence of physicality strips away essential elements of the art experience. The smell of paint, the texture of a canvas, the serendipitous encounters between strangers in a crowded gallery—these are nuances that even the most advanced virtual environments struggle to replicate. Proponents, however, counter that the metaverse offers its own set of sensory and social possibilities. Spatial audio can create intimate soundscapes, haptic feedback can simulate touch, and avatars can facilitate interactions that transcend language barriers. The debate underscores a broader cultural reckoning with what we value in artistic encounters and whether new forms of engagement can coexist with—or even enhance—traditional ones.

As the Metaverse Biennale continues to evolve, it serves as a testing ground for the future of cultural production. The lessons learned here extend beyond the art world, offering insights into education, commerce, and social interaction in virtual spaces. Whether this experiment will eventually replace physical exhibitions or simply exist alongside them remains an open question. What is certain, however, is that the boundaries between the real and the virtual are becoming increasingly porous, and the ways we create, share, and experience art will never be the same.

By Eric Ward/Apr 12, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 12, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 12, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 12, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 12, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 12, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 12, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 12, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 12, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 12, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/Apr 12, 2025