The cosmos has always been a source of inspiration for artists, but rarely has science and art collided so vividly as in the emerging trend of transforming exoplanet atmospheric spectra into stained glass masterpieces. What began as an academic exercise in data visualization has blossomed into a full-fledged artistic movement, with glass artisans and astrophysicists collaborating to translate the chemical fingerprints of distant worlds into radiant panels of colored light.

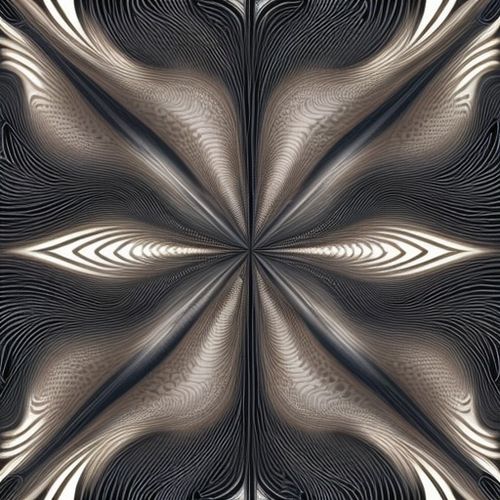

At the heart of this phenomenon lies the science of spectroscopy - the practice of separating starlight filtered through alien atmospheres into its component wavelengths. Each dip and spike in these spectral graphs corresponds to specific molecules absorbing light, creating what researchers call "chemical bar codes" for planets orbiting other stars. Where scientists see data points indicating water vapor or methane, artists like Elara Montague see cascades of sapphire blue and emerald green. Her studio in Barcelona has become ground zero for what she calls "astrochemical vitreography," with each commissioned piece requiring months of painstaking translation from scientific charts to glass compositions.

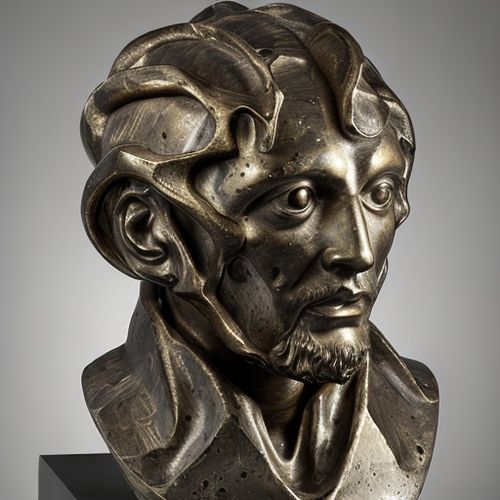

The technical challenges are as fascinating as the artistic results. Traditional stained glass techniques, perfected over centuries for ecclesiastical windows, must adapt to represent scientific accuracy. "You can't just pick pretty colors," explains Dr. Hiro Tanaka of the Exoplanet Spectroscopy Institute. "The exact wavelength absorbed by sodium atoms on WASP-96b translates to a very specific yellow hue that must be matched in the glass composition." This precision has led to collaborations with glass chemists who can replicate the light-filtering properties of atmospheric gases in physical materials.

One remarkable example currently on display at the London Science Museum is a 2-meter interpretation of HD 189733 b's atmospheric spectrum. The cobalt blues representing Rayleigh scattering blend seamlessly into the deep reds of silicate particle absorption, creating a visual narrative of the planet's violent winds. What appears as an abstract composition actually tells the precise story of how light interacts with this alien world's atmosphere, with each glass segment's opacity and texture corresponding to absorption line intensities.

Beyond their beauty, these works serve an important educational purpose. The three-dimensional nature of stained glass - with its varying thicknesses, textures, and lead lines - can convey complex spectroscopic concepts more intuitively than textbook graphs. Visitors to the Montague Studio's exhibitions often report suddenly understanding atmospheric composition in ways that eluded them during physics lectures. The play of natural light through these panels recreates the very phenomena they represent, as sunlight interacts with the colored glass much as starlight interacts with exoplanet atmospheres.

Purists in both the art and science communities initially questioned the value of such hybrid creations. Art critics dismissed early attempts as "data decoration," while some astronomers worried about oversimplification. However, the movement has gained credibility through rigorous attention to scientific detail. Each piece undergoes peer review by the originating research team, with some installations even including QR codes linking to the original spectral data and published papers.

The commercial art market has taken notice, with collectors paying premium prices for these cosmic interpretations. A recent auction at Christie's saw a triptych based on TRAPPIST-1 system spectra sell for £240,000, signaling serious demand. More importantly, the trend has sparked interest in funding spectroscopic research, as donors seek to immortalize their favorite exoplanets in glass. The Kepler Foundation now offers naming rights for newly discovered worlds to patrons who commission artistic interpretations.

Looking ahead, practitioners envision entire architectural projects based on this concept. Plans are underway for a "Galactic Cathedral" in Reykjavik, where stained glass domes would represent hundreds of known exoplanet atmospheres arranged by discovery date. As telescope technology advances and we gather more detailed spectra from smaller, Earth-like worlds, the artistic interpretations will grow increasingly nuanced. What began as decorative data visualization may well evolve into a lasting artistic legacy of humanity's first era of exoplanet exploration - a colorful testament written not in ink or pixels, but in light filtered through glass, much like the distant atmospheres they portray.

By Eric Ward/Apr 12, 2025

By James Moore/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By John Smith/Apr 12, 2025

By Michael Brown/Apr 12, 2025

By George Bailey/Apr 12, 2025

By Sophia Lewis/Apr 12, 2025

By David Anderson/Apr 12, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Apr 12, 2025

By Grace Cox/Apr 12, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 12, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Apr 12, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 12, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Apr 12, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Apr 12, 2025

By Laura Wilson/Apr 12, 2025

By Natalie Campbell/Apr 12, 2025